TLDR: when writing new material for a system like Troika!, don't be fooled by system simplicity. Smaller systems are often more tightly crafted and therefore easier to "break." Also, I have taken some heat for this one – so don't take it too seriously; I don't mean to crap on your fun.

|

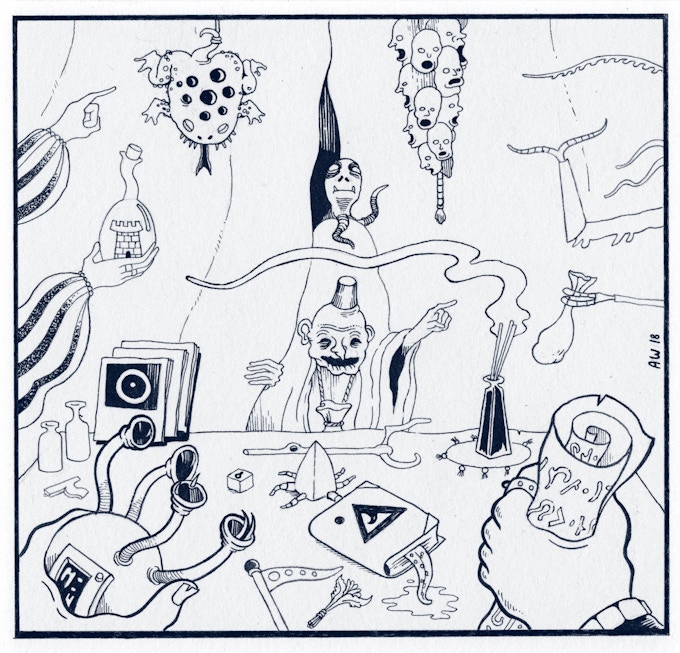

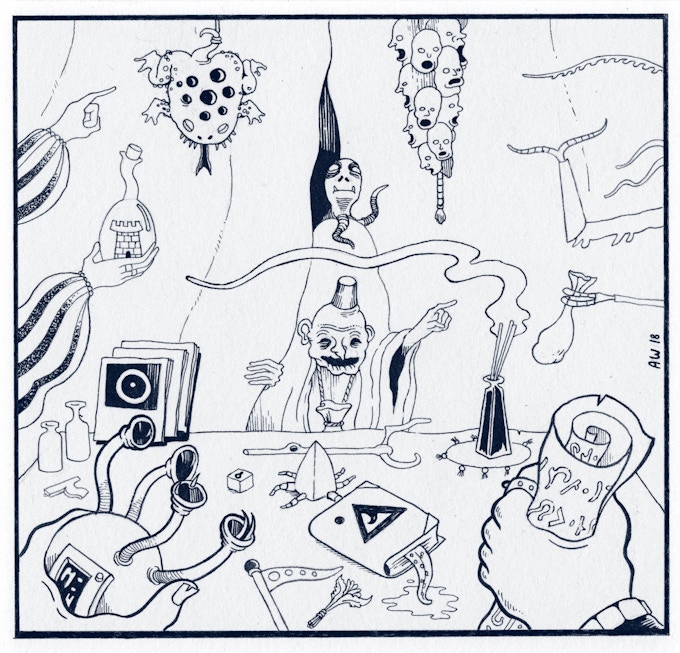

| Troika! art by Andrew Walter |

I recently ran a few sessions of

Troika! by Daniel Sell. Having read it over a several times, made my own notes/cheat sheets, and even written some material for the game as well as having run it, I feel like I can make some comments on the system's core architecture. I wouldn't consider it to be a particularly deep system, or I wouldn't even attempt this kind of statement after only a few outings at the table!

That's the "what" of this article. The "why" is because

Troika! is very "hackable" and I see people out there writing material for it, mainly new backgrounds or creatures, with what appears to be (in some cases) almost no understanding of the system. By that I mean, individuals are writing things in such a way that it runs counter to the basic construction of the system, is not intuitive within the context of the system, and ultimately may be destructive to the play environment of the game.

Edit – I kind of wish I had written this article from the viewpoint of "those who got it right!" instead of angling at those who made what I consider to be a mess. But it is what it is.

Here are the core tenets as I see them, in no particular order, each concluding with a statement about how I believe they should affect one's design-brain.

Based on 2d6

Perhaps it would be more accurate to say the game uses only d6s to accomplish all of its goals.

"There is only one die type used in Troika!, that being the d6" (40).

Most player actions are resolved with a roll of 2d6, usually under a skill or versus an opposing roll. In addition to that, all randomness in the game is based on six-sided dice. Creature reactions (miens), for instance, are expressed in a d6 table. And one rolls for a background using d66 (two d6s rolled in the manner one rolls two d10s to get d100, which is to say one die for tens and one for the singles).

Rolling 2d6 gives you a curve whereas rolling d66 (or d6, or even d36) generates an even distribution. But since rolls other than 2d6 are used exclusively for random table stuff, not task or combat resolution, I think we can safely say that the success of actions in the game are more predictable than in a flat d20 style curve. It's easier to figure your odds of success in a d20 universe as every 'pip' represents a 5% swing, but it's easier to predict actual success or failure when a curve is in play. The 2d6 results of 6-8 occur 44.5% of the time! That's aside from the main point I want to make, however, which is...

Avoid creating material for Troika! that uses dice other than d6s. It just feels odd. The game was written in the spirit of using "common" dice. While it's easy to argue that all the polyhedral are common these days, there's something simple and elegant about sticking to the cubes.

Backgrounds over Setting

Troika! builds an implied setting using the 36 (d66) backgrounds included in the core book. We know there are "golden barges" that carry passengers between the "crystal spheres" primarily because there are references to them in the backgrounds for Cacogens, Lansquenets, and Thinking Engines. We encounter spell magic first in the Befouler of Ponds background, and in several dozen other backgrounds as well, before we get to the mechanics of spellcasting or the spell descriptions. Creatures, items, and spells are other places where setting is created, but they are usually foreshadowed in backgrounds. I.e. Gremlins are foreshadowed by the Gremlin Catcher, demons by the Demon Stalker, and guns by the Cacogen, Lansquenet, etc. Consider that the Chaos Champion has in his possessions list ritual scars and a nearly full dream journal! Those add ideas as to what a Chaos Champion is – how he lives, thinks, and acts. It's marvelous stuff.

Conversely, or perhaps consequently, there are no text-heavy passages of pure setting and every item that might be categorized as setting has direct rules implications. While a spell listing may or may not contain stats, it is something that directly affects the fictional world when brought into play. There are no instances that run contrary to the "Chekhov's Gun" principle. If a thing is represented, it is intended for use; there are no purely ornamental set decorations, which is a bit of a shock given how baroque Troika! feels.

Utilize backgrounds and tables to build the world; avoid writing pages of setting lore. Caveat: I'm talking about material you would write to publish or otherwise share with others. Your home campaign is a different story, literally, and it's where you will/should build out fiction through play.

Skill Specificity

Some have described the skill system in Troika! as a mess. I don't believe that is the case. It is true that there is no exhaustive taxonomy of skills, as one sees in most traditional RPGs – any that feature skills at least. The book encourages you to make up new skills as needed without a lot of guidance as to how, or how narrow they should be. However, even though the skill list not thorough, the skills that are given display a consistent level of specificity. There is no catch-all "fighting" skill, only skills like "hammer fighting," "wrestling," or "fist fighting."One can assume a character that has advanced skill in fighting with fusils, would not be especially trained in bows, even though both are missile weapons. Hence the need for a default Skill stat, which represents a kind of natural dexterity or deftness of mind, and advanced skills to represent training. Writing a new skill that is too broad; e.g. weapons or logic, erodes backgrounds (by trumping a more specific skill) and makes the game more boring (applies to too many situations).

Be mindful when you write skills. Make them sufficiently narrow/situational. Broad skill concepts are baked into the base Skill statistic. I have seen cogent arguments for dividing Skill into Mental and Physical, which seems cool to me but I wonder where it stops if you start dividing it. Pretty soon you would have six skills: STR, INT, WIS ... oh dear. I've also seen variants on Troika! that do away with base level Skill and only have specific/advanced skills.

Interaction Over Combat

Only three spells specify damage and many backgrounds lack an advanced skill in any form of fighting. 'Nuff said? If players want to fight, they will. The Assassin's Dagger spell can be used to send a poisoned blade after a target, but it can also be used to send a message scroll. Troika! is heavily focused on exploration and imagination, partly because it leaves so much white space that players can/must fill with their own inventions and partly because what is provided is often already weird.

Whenever possible, create material that is flexible – without a narrow focus on combat. Resist the urge to make combat more fussy/bloated than it already is.

Summary

Troika! is a different animal. You get that from the minute you pick up the book. While feeling very ornate with it's bizarre art, high-end production values, and exotic backgrounds, the underlying core is a lean, mean machine. The game's exotic flavor and simple mechanics are married like two sides of a coin. You can't write new mechanics without writing new flavor and vice versa. So be mindful when you create; hew closely to the established patterns unless/until you have a deep enough understanding of the game to break those patterns.